A collection of rare photographs has recently come to light

Valdonë Kupstaitë

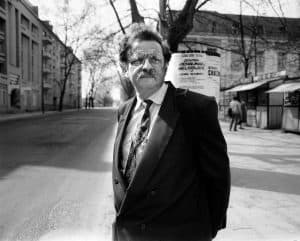

Last year, to mark Sartre’s 100th birthday, a photography exhibition traveled round several European cities. The photographs had been taken by the then unknown 26-year-old photographer Antanas Sutkus, during Sartre and de Beauvoir’s trip to Lithuania in 1965.

Since then, the photographer himself has achieved world recognition. He has held over 60 solo exhibitions and published 14 books. Now, at 66, is a holder of three Grand Prix and three FIAP gold medals. In his own country, he is perhaps the best-known photographer.

***

If you have ever visited the Bibliothéque Nationale in Paris, on entering the courtyard, your eye should have been caught by an expressive bronze sculpture of a bent figure fighting against wind and sand.

This sculpture of Jean-Paul Sartre, by the French artist Roseline Granet, has a story, which started in the mid-1960s in Lithuania, which was then one of the republics of the Soviet Union.

Entourage

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir came to Lithuania in the summer of 1965 for a one-week visit. At that time, it was impossible for visitors to travel independently to the USSR. Of course, the journey was carefully planned, supervised and monitored by the state. And even the group of young intellectuals who accompanied the couple during the trip were chosen by the authorities.

By chance, among them was the then unknown 26-year-old photographer Antanas Sutkus. Shortly before the arrival of the couple, he managed to join the official delegation of writers who were accompanying the famous visitors.

In this way, from the very moment Sartre and de Beauvoir arrived, their tour was chronicled. He did it using his modest and discreet Zenit camera, as if he was just an onlooker, as a supplement to the conversations on literature, to which he was also a party.

This resulted in a unique record, consisting of nearly 100 photographs. While presenting a record of the tour, they also recreate the atmosphere of those days.

Sutkus was concerned primarily with making a psychological study of the two guests, rather than his role as a reporter and chronicler. Everything is genuine, as he did not use any props, lighting or montage.

The clouds beneath his feet

Everyone wanted to photograph Sartre. Normally he only allowed well-known photographers, such as Brassai, Freund and Cartier-Bresson. They took studio portraits, and never snapshots.

They never accompanied him on trips to the Soviet Union (the philosopher visited the country 11 times). So from all these trips, except for the famous photograph with Khrushchev in 1964, there remain very few documents.

Thanks to Sutkus, we have not only a collection of portraits, but also photographs registering the inner and harsh contradiction in Sartre’s physical presence.

In one of his works, through photographic imagery, he interprets convincingly Sartre’s ideas of “being and nothing”, and individual freedom. In the white desert of sand, his dark and powerful silhouette moves from nowhere to nowhere along the horizon.

Sutkus’ photographs tell a story. It starts with the arrival at the airport in Vilnius. Sartre and de Beauvoir had asked to make an unofficial, private visit. That is why the reception was kept simple and very personal. The two were welcomed with bouquets of white marguerites.

Their first destination was Nida and the Curonian Spit, a thin sandy peninsula flanked by water.

“Nature seemed to overwhelm them,” Sutkus recalls. “They were townspeople, and seemed a little lost in their smart shoes and their urban clothes, fighting against the sand and the wind in the dunes.”

Once, Sartre sat down on the top of a dune, and took off his shoes in order to let out the sand. Simone de Beauvoir walked barefoot, carrying her bag in one hand and her shoes in the other.

“One day, Sartre suddenly stopped, took a look around, and said: ‘That’s like the doorway to paradise.’

“We were standing on the peak of a dune. Beneath us, just above the surface of the sea, the clouds seemed like cotton wool. Sartre smiled, and said: ‘This the first time I have walked with clouds under my feet!’”

In most of the photographs, Sartre and de Beauvoir are presented separately. Apparently, no conversation or eye contact with other members of the group took place. There was no communication.

At the beginning, the members of the group felt like people who had happened to be in the same place at the same time by accident. Possibly it was the stunning landscape around them that made them so silent.

“The Lithuanian writers were close friends,” Sutkus recalls. “And, even if we admired Sartre, existentialism was after all a philosophy of young intellectuals, so we were not intimidated by him. He didn’t talk much, but he was completely down to earth and friendly.”

Sartre didn’t notice for a long time that Sutkus was taking pictures. The photographer always talked about literature, and he only had a small camera. Sartre was used to professionals who worked with big Nikons. Besides, Sutkus never asked him to pose.

“Once, when I was taking pictures of him in a restaurant, he asked me not to take pictures while he was eating. I jokingly said: ‘I won’t take pictures of you eating, but of you smoking and drinking.’”

Interested in more Latest News from Lithuania? Check this article.

Two women

Even those who know nothing about Sartre’s personal life can feel from the photographs that the two weren’t very close. They show that they were together, but at the same time they followed their own paths. There was no love left between the two after all those years.

Sartre’s relation to Lena Zonina, the Russian interpreter, was better than with Simone de Beauvoir. Zonina, who was not only an interpreter but also an intelligence agent, always seemed closer to him than de Beauvoir did.

Zonina, who had an excellent knowledge of French and was a specialist in French literature, had translated The Flies and Words, and had managed to obtain from Sartre an excellent preface to the translation of the latter work.

“Only later did I realise that Zonina had always tried not to appear in the pictures,” says Sutkus. “Today, it is not a secret any more that Sartre and Zonina liked each other a lot.

“A few times she is seen very close to Sartre, and, astonishingly enough, also getting on well with Simone de Beauvoir. It is quite amusing how Zonina copied de Beauvoir in her dress and her hair. It also shows how well everything had been planned in advance by the authorities.”

Sartre was always accompanied by a group, and never got to know people who were outside it. He was enthusiastic about Lithuania, but he didn’t know that not everything was as beautiful as it appeared to be. They only showed him the sunny side of life.

Local journalists covered the trip with great respect and appreciation. Shortly after his return to Paris, Sartre wore a Mao badge while participating in a student demonstration. Since the Soviet Union and China were enemies, after that incident Sartre was declared persona non grata in Lithuania.

Truth and shadows

The most famous picture that Sutkus managed to take of Sartre shows the philosopher in the dunes as a dark silhouette. He is leaning against the wind and fighting through a no-man’s-land.

“The photograph has something laconic and existentialist about it. I took it subconsciously. I think the existentialist idea inherent in the picture would come across, even if Sartre were not in it.”

The atmosphere of the pictures seems relaxed, calm and almost intimate. Since there were no big official events happening that week, in the photographs every little detail and every tiny gesture is given a special meaning.

It is a sort of genre photography, captured with the camera during the trip, as in his main work, called “People in Lithuania”.

“I can only take pictures of people I know. I am very familiar with people in Lithuania. I have spent my life with them, since I was born. I have an archive of more than half a million negatives. They all show moments of everyday life.

“Having read his books, I felt very close to Sartre. That’s why it was not very hard for me to relate to him, to build up a rapport. And I was very taken by his personality. I was impressed at him being such an easygoing man, this great philosopher!

“Artists in the Soviet Union always behaved like priests; they were inaccessible, and they always talked in loud voices.

“Sartre, on the other hand, was very open and modest. And not at all vain. There are several portraits that show him looking cross-eyed. But it never bothered him; he still liked those ones. He rarely laughed, but he had a great sense of humour. All this made it quite easy to approach him with the camera.

“With Simone de Beauvoir, it was more difficult. I hadn’t read anything of hers. But she struck me with her cordiality and warmth.”

After the visit, Sartre asked Sutkus to send him prints. It was done with the help of Zonina, who took them to Paris. She visited him several times, and said that he liked them a lot. Sartre continued to send him greetings for a long time.

Some time later, Sutkus sent his picture “Sartre Fights against the Wind in the Curonian Spit”, without any signature, to France, to the director of the VU photograph agency in Paris.

“Nobody believed the photograph was mine,” he recalls. “They called me a cheat. They gave the credit to Cartier-Bresson.

“After returning to Vilnius, I rummaged through my studio, together with my assistant, looking for the negative. Finally, I found it, printed a contact sheet, and sent it to Paris. After that I was rehabilitated.”

There are two versions of that famous picture. One shows Sartre and the shadow of Simone de Beauvoir, and in the other you see her in person. Sutkus only published this version in order to prove that it really was his. Some people assumed that the shadow was that of a KGB tail, but it was de Beauvoir.

“For the version that later became famous, I cut her out. The composition bothered me. With the two in it, it expressed everyday life. It changed character completely. Sartre alone is the metaphor for his philosophy.”

A man on the horizon moving from nowhere to nowhere. Being and nothing. The ultimate individual freedom of the human. The picture has become something like Sartre’s calling card.