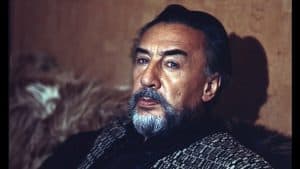

Romain Gary, twice winner of the Prix Goncourt, based parts of his early Books on his childhood in Vilnius

One of the most interesting and colourful 20th-century French novelists was to say about Vilnius: “Perhaps it was here that I was born as an artist.”

Romain Gary (his real name was Roman Kacew) was born in the city on 8 May 1914. Later living in Russia with his mother for a while, he returned to Vilnius for a few years (from 1917 to 1924), and spent several crucial years of his childhood and adolescence at 16 Wielka Pohulanka Street (now Basanavičiaus gatvė 18).

After a one-year stay in Warsaw, he at last reached France, the country of his dreams, to begin to turn into what, in his childhood, his mother had predicted, or rather told him, to be. Become a writer, and not an ordinary one, but a winner of the Prix Goncourt. Twice, as it was to turn out.

In the literary world, Gary committed the only instance of a bizarre feat. The Prix Goncourt is awarded to an author only once. Gary received it the first time in 1956, for his book Les Racines du ciel (The Roots of Heaven). However, in 1976, under the pseudonym Émile Ajar, he won it again, for his book La Vie devant soi (Your Life ahead of you).

A Life

The life of this writer is like a literary work itself. From childhood, it was an unending search for harmony, tenderness, love, and the absolute. While still a child in Vilnius, he received his first lessons in love from his mother, which would guide him throughout his life.

“It is not good to be loved so much so young, so soon. You develop bad habits. You think that this is it. You think that it exists elsewhere, that you will find it again. You expect it. You look, you hope, you wait. With your mother’s love, life makes you a promise at the beginning which it will never keep. You are then forced to eat cold food until the end of your days. After that, every time a woman takes you into her arms and holds you against her heart, it is no more than condolences … Adorable arms wrap around your neck, and very tender lips speak to you about love, but you know the truth …” (Promise at Dawn).

It was in Vilnius that his mother decided (to the amusement of the neighbours, she actually shouted it out loud), that Romain would be a French ambassador, a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur, a great playwright, Ibsen, Gabriele d’Annunzio. And … that he would have his clothes made in London! The greatest possible success. And he achieved it all. Regardless of his distaste for the English cut, Gary had his clothes made in London (“I have no choice”).

Having graduated from an aviation school in France just before the Second World War (before that he had trained as a lawyer in Nice), during the war he participated in air battles as a co-pilot, and was awarded the Légion d’Honneur and the Croix de la Libération, and became a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur.

France then sent the young Romain to join the diplomatic service, in which he served successfully for 15 years: in Bulgaria, Switzerland, Bolivia and the United States (consul general in Los Angeles, and at the UN headquarters in New York).

As he was to write himself, he most enjoyed Bulgaria (it was his first posting, immediately after the war) and Los Angeles. The most boring posting was Bern, in Switzerland, where it was too sterile, too orderly.

“No memories. In my mind, a void of a year and a half. As if through a mist, I recall some kind of clocks in towers, which strike the hour, or something like that. Bern gives people a strange impression. It certainly is the most mysterious city on earth, a kind of Atlantis, which is still to be discovered. It seems that life is … somewhere else. In the end I sent an encoded telegram to Bidault [the Foreign Minister] in Paris:

“ ‘I have the honour to inform Your Excellency that at 13.00 hours it snowed in Bern for 20 minutes. It should be noted that this snowfall was not mentioned by the Swiss meteorological service, and I leave Your Excellency to draw the appropriate conclusions.’

“Bidault did so, and said to Bousquet, the head of the personnel department: ‘Send him to the loony bin.’ That’s how I got my posting to the UN in New York as a spokesman” (from La nuit sera calme).

In 1961, once again, Gary made a radical change in his seemingly steady and successful life, and resigned from all his diplomatic posts. At last, having met Jean Seberg, a woman whom he had predicted very precisely and described in Les Couleurs du jour (The Colors of the Day), a young and already very popular film star (whom cinemagoers in Europe may remember from the memorable New Wave cult film by Jean-Luc Godard “A bout de souffle”), he devoted himself exclusively to writing.

Under the effect of Hollywood’s charm, he wrote for the cinema, directed several films, travelled, wrote books and reports, brought up his son Alexandre Diego (after divorcing Jean in 1970, the son stayed with his father), and gradually became entangled in a growing literary scandal of his own invention, regarding the mysterious Ajar. Gary sank deeper into depression.

The speculation as to who Ajar was, which was comparable to the scale of that of the Dreyfus Affair, the fear of growing old, the death of Jean (she had committed suicide in 1979), came to a head on 2 December 1980. Having written a note with the words “at last, I have probably said everything,” Gary shot himself with his revolver.

According to his wishes, the book Vie et mort d’Émile Ajar was published only after his death, in 1981. It gives an explanation of the riddle, and discusses his constant striving for distraction, his insatiable thirst for life.

About Vilnius

Vilnius was a special city in Gary’s life. In his autobiographical La Promesse de l’aube (Promise at Dawn), published in 1960, he describes the city between the two world wars. Many of its pages are devoted to people, streets, backyards and the house where he lived. And all this was written down with such humour and love for the city and his mother, that literary historians consider it the most beautiful bouquet of flowers in 20th-century literature written by a son to his mother.

Today, Gary’s Vilnius is already rather distant and exotic, and at the same time so familiar (especially to those who grew up in the postwar years), still perpetuating itself. The backyards, games and adventures, as though connecting time, urging children to come home to dress in their Sunday best, in order for the family to look respectable enough to show itself to people, and to get back quickly to freedom, are all familiar.

This was a real school of life, interesting and lively. It was in Vilnius that the nine-year-old Romain fell in love for the first time. Eight-year-old Valentina was bright eyed, perfectly formed, and wore a white dress.

Having decided to charm her instantly and forever, “to leave no space for any other man in her life”, he tried everything, from rolling his eyes (his mother explained that women would be driven wild by his blue eyes) to eating worms, leaves, snails and butterflies in order to win her attention. Finally, after eating a rubber boot, he felt the admiring look of the “lady”, before being taken away in an ambulance, and had just enough time to feel that he had “really become a man”.

It was in Vilnius that he felt the need, the dream, the first flush of his desire to overcome everything.

The aspiration with which “humanity fueled as well as its worst crimes, also its museums, its poems, its empires … This is how I became familiar with the absolute, of which I will undoubtedly keep in my soul until the very end a profound gap, like the absence of someone. At that time, I was only nine, and I could not foresee that I was feeling for the first time the caress of what more than thirty years later I was to call ‘the roots of heaven’ in the novel with the same title. The absolute suddenly announced to me its unattainable existence, and I did not know in what spring I could quench my passionate thirst. There is no doubt that it was on that day that I became an artist.”

For current Lithuanian News in English see this article.

That Gary knew Vilnius and the region, and not just episodically, in passing, becomes clear from his first book, which brought him international fame. With the war still raging (it was 1944), it was read out on the liw.lt World Service, and later published in many languages.

Jean-Paul Sartre was to call L’Education européenne the best book written about the Resistance. The book contains not only a detailed description of Vilnius, but also of the region, with its people, character, streets, villages and names.

It is significant that a monument to the famous resident of Vilnius, which is soon to be unveiled, will stand in front of the house described in La Promesse de l’aube. A boy presses a boot to his heart, and is about to start eating it in the name of his beloved neighbour, Valentina. Not far from here is a small café called the Romain Gary. There is also the writer’s fan club.

It is a tribute to Gary, a humanist, writer, and former resident of Vilnius. It is continuity. “I view life as a long relay-race, where each of us, before falling down, must carry the challenge of being man as far as he can.”